“A la brida” and “a la gineta.” Different riding techniques in the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance

(in Pirro Antonio Ferraro, Cavallo frenato, Napoli, 1602)

by Giovanni Battista Tomassini

Defining, in his Book of the Courtier (1528), the ideal features of the Renaissance gentleman, Baldassare Castiglione wrote: “I would hope that our Courtier is a perfect horseman in every kind of saddle” (1, 21). That a gentleman had to be able to perfectly ride a horse is quite obvious. Since the Middle Ages, and for many centuries thereafter, the practice of knightly exercises represented one of the characteristic features of the identity of aristocracy. So much so that the term “knight” came to be identified with that of “noble” as a synonym. What is instead striking is the reference to the different types of saddles. This was a suggestion that the author did not explain, considering it clear to his contemporary readers, but which now seems far less apparent, giving us the opportunity for a quick overview of the main equestrian techniques practiced at the time.

Louvre Museum – Paris

It is evident that, if it was only a matter of harness, Castiglione’s specification would have been superfluous. In fact, as we will see in more detail, the author of the Book of the Courtier refers to different riding techniques which characterized equitation in late medieval times and during the Renaissance. We find a clear testimony of these different techniques in the most ancient equestrian treatise of the post-classic age: the Livro da ensinança de bem cavalgar toda sela. This is the work which Edward (Duarte), King of Portugal (1391-1438), wrote around 1434 and which was handed down to us in a manuscript, first published in Paris, dating back to 1842. The title can be translated into the Book of the art of riding with any type of saddle. We then find the same premise discussed in Castiglione, but in this work, the author gives us many more details.

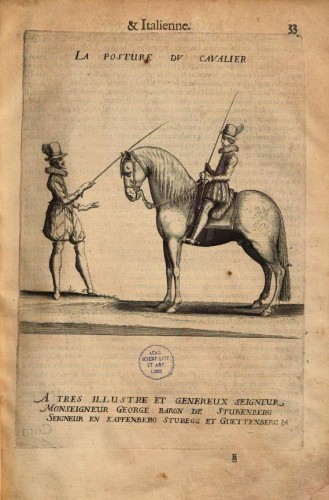

and the feet forward

(in Pierre de la Noue, La Cavalerie Française et Italienne, Paris, 1620)

In his book, Dom Duarte distinguishes five different ways to ride a horse: 1) the one with the Bravante saddle, 2) the one in which the rider does not take support on the stirrups, 3) the one in which the rider stands firm on the stirrups, 4) the one in which the rider rides with short stirrups, 5) and finally, riding bareback, or with a pack-saddle without stirrups. The distinction, according to the type of the saddle and to the length of the stirrups, clearly refers to different ways in which the rider is seated and then to different riding techniques. Dom Duarte says that the habit of riding nearly without resting the rider’s feet on the stirrups was widespread in England and in some Italian regions, while riding without stirrups and no spurs was typical of Ireland. According to Carlos Henriques Pereira, who devoted detailed studies to Dom Duarte’s book, the first and the third way mentioned by Dom Duarte substantially coincide and correspond to the so-called “a la brida” style, which was frequently mentioned in later treatises. In fact, as we will see, these two ways of riding were very different and can be compared only by the fact that the rider rode keeping his legs straight. These ways of riding were opposed to the so-called “a la gineta” style, characterized by the fact that the rider rode with shorter stirrups and bent legs. Even though Dom Duarte’s classification demonstrates the coexistence of many different riding techniques in the late medieval period, equitation at the time and during the Renaissance was mainly characterized by the contrast between the a la brida and the a la gineta styles.

The “a la brida” style was the typical technique of heavy cavalry and was characterized by the use of long stirrups. As we have already seen, Dom Duarte distinguished two different methods: the first one was done with a particular kind of saddle, called “Bravante saddle”, and consisted of riding deeply seated, keeping the feet forward (III, 2); the second, in contrast, consisted of riding standing up in the stirrups, never sitting on the saddle (III, 4). To facilitate this second method, the stirrups were fastened to each other with a strap under the horse’s belly in order to prevent them from separating. According to Dom Duarte, the method of standing while riding was older and required the rider to keep his legs perfectly straight under him. Both of these techniques were used to facilitate the knight in handling the lance. Between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the length and the weight of this weapon increased progressively. This required the rider, who was already awkward in his movements from heavy armor, to stand firm in the saddle in order to face the moment of collision with his opponent. For this purpose, special saddles with very high pommels and cantles were used in order to support the rider. According to Carlos Henriques Pereira, and to other historians, the “a la brida” style was typical of Northern Europe. But it is well documented that this way of riding was also widespread in southern countries such as Italy and also in Portugal. Indeed, according to Baldassare Castiglione, Italian knights stood out because of their ability in this technique and for their ability to master difficult horses.

“it is the special pride of the Italians to ride well a la brida, to school wild horses with consummate skill, and to play at tilting and jousting.” (Book of the Courtier, I, 21)

(in Johann Jacobi von Wallhausen, Ritterkunst, Franckfurt, 1616)

In addition, this was the typical riding technique used in jousting, the knightly games in which two armed knights on horseback faced off at “the barrier,” if between the two contenders, there was a “tilt,” made of wood, or of canvas, or in the “open field.” These chivalrous events were widespread throughout Europe up until the seventeenth century and this explains also why “a la brida” was a common style.

which were widespread throughout Europe

(in Anthoine de Pluvinel, L’instruction du roy en l’exercice de monter à cheval, Paris, 1625)

© The Trustees of the British Museum

In contrast, the “a la gineta” style of riding with shorter stirrups, allowed the rider a more direct and precise contact of the “lower aids” with the horse’s sides. According to Dom Duarte, this style required the rider to sit “in the middle of the saddle”, not using the support of the pommel and the cantle, keeping the feet firmly resting on the stirrups, with the heels slightly down (III, 5). It was a technique typical of the Iberian Peninsula, clearly originating in North Africa. The term “gineta” or “ginetta” comes from the Spanish word “jinete” which, in turn, most likely derived from the Berber tribe of Zeneti, famous for it’s light cavalry. They would have been the ones to introduce this style of riding to the Iberian Peninsula. This origin is also clearly identified by the fact that in the “a la gineta” style, a kind of bit was used which was identical to those still in use in North Africa. It was formed by two short shanks connected by a cannon, with a central shovel that rested flat on the horse’s tongue and on top of which a large metal ring was attached. This ring passed under the lower jaw of the animal and acted as a curb chain. Also, the saddle was clearly of Arabic origin and was quite similar to the “silla vaquera” still used in Spain.

allowed the rider a more direct and precise contact

of the “lower aids”

(in Galvão de Andrade, Arte da cavalaria de Gineta, Lisboa, 1678)

The “a la gineta” style was typical of the Iberian Peninsula, but rapidly spread into the domains of the Spanish Empire and particularly into southern Italy, where the horses of Spanish origin were called “Ginnetti”. We find testimony of the widespread breeding of this kind of horse in the southern regions of Italy, in the frescoes of Palazzo Pandone in Venafro. Among these frescos is the portrait of the bay “ginecto” called Stella, portrayed at the age of four on the 23rd of May 1523, which was subsequently donated to the Neapolitan nobleman Annibale Caracciolo. Dom Duarte underlines that riding “a la gineta” was not practiced in Northern Europe and that the British and the French had little experience with this way of riding (III, 7).

Riding “a la gineta” is also the basic technique of bullfighting on horseback. The short stirrups allowed the rider to make fast stops and departures, as well as sudden changes of direction, which are essential in the fight with the bull. It is well known that this kind of fighting took place not only on the Iberian peninsula, but during the Renaissance, was used as well in Italy. Benedetto Croce recalls events in Siena and Florence, where, in 1584, in Piazza Santa Croce, there was a magnificent bullfight on the occasion of the visit of Prince Vincenzo Gonzaga, heir to the throne of Mantua. Maria Bellonci chronicles the passion of the Borgias for bulls and mentions the bullfight with which the Duke Valentino, Cesare Borgia (the son of Pope Alexander VI), celebrated the New Year’s Eve 1502, no less than in Saint Peter’s square in Rome. The features of the “a la gineta” style were also further used in some types of chivalrous trials, such as the “game of the reeds” (juego de canhas) and the “carousel joust.” They both were equestrian games of Arabic origin, imported by the Spaniards in Italy, in which two teams of riders faced each other in a bloodless battle armed with reeds and Moorish shields, or hurling projectiles made of clay.

(Antonio Tempesta, Caccia al toro, 1598)

However, both Dom Duarte and, about a century after him, Baldassare Castiglione were convinced of one thing: the perfect knight must master each of these techniques and be able to adapt to any type of saddle, since each one is useful for specific needs. “A man will never be a good rider if he is not able to choose the most appropriate way to ride on each type of saddle” (Livro da Ensinança de Bem Cavalgar Toda Sela, III, 14).

(in Pirro Antonio Ferraro, Cavallo frenato, Napoli, 1602)

Bibliography

BELLONCI, Maria, Lucrezia Borgia, Milano, Mondadori 1939.

CASTIGLIONE, Baldassare, Il Cortigiano, a cura di A. Quondam, Milano, Mondadori, 2002.

CROCE, Benedetto, La Spagna nella vita italiana durante la Rinascenza, 2a ed. riveduta, Bari, Laterza, 1922.

D’ANDRADE, Fernando Sommer, La tauromachie équestre au Portugal, Paris, Michel Chandeigne, 1991.

Dom DUARTE, The Royal Book of Horsemanship, Jousting and Knightly Combat, translatetd by A. F. and L. Preto, edited by Steven Muhlberger, Highland Viallge, The Chivalry Bookshelf, 2005.

PEREIRA, Carlos Henriques, Etude du premier traité d’équitation portugais. Livro da ensinança de bem cavalgar toda sela, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2001.

PEREIRA, Carlos Henriques, Naissance et renaissance de l’equitation portugaise, Paris, l’Harmattan, 2010.

21 Comments

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

molto, molto interessante

Interessante, così come il libro “Le opere della Cavalleria”. Bravo.

Cari Alessandro e Pino,

grazie mille per il vostro apprezzamento.

Grazie del link, ora ho capito tutto 🙂 seguirò il blog !

Grazie a te Andrea, per l’interesse e l’apprezzamento. A presto

Dear Sir,

Thank you once again for some superb work.We in England are celebrating Newcastle by displays in his riding house and I would very much like you to see one if you have the time? Thank you for the display of patterns and esp the illustrations with music!

Kind regards,

Dominic Sewell

Dear Dominic,

your appreciation makes me very happy. I would be very pleased to see how you celebrate the genius of Newcastle. I visited your website http://www.historicequitation.com/, but I could not find information on the subject. Where can I find some more news?

Hello, very well written and interesting. Fernando Sommer was a very close friend of mine during the years I lived in Portugal (and after). Happy to talk to you when you want.

Arrivederlo. Jean Philippe Giacomini

Dear Jean Philippe,

thank you very much for your appreciation. I’m glad that you enjoyed my article and I hope that you will want to further explore my blog to know the other contents. Even I’ll be happy to keep in touch with you and talk about our common passion for horses and classical riding. I’m sure we have much to share. I hope to read you soon again. Bye!

Andalusian Horse Guide I love this helpful information people give in your articles. I’m going to search for your current site and also test out all over again the following often. I am relatively sure I will likely be shared with many new goods right right here! All the best for the following!

Very interesting article and exceptional documentation and bibliography. I was always thinking that the ”a la brida” riding is more suited to ambling horses .The ”ginetta” style with short stirrups is more common in galloping horses. Ambling was a way of mooving that was very common to every kind of horse in medieval times .We see it in Byzantine icons, Italian , French , Polish, etc . Science has prooved that it is a gene in many breeds, The ambling gait , [which today is ”gaited”] is generaly much more comfortable for the rider than the trot because the frequency of it is much shorter . The typical way to ride gaited horses is to sit ”deep” with legs extended and the fastest it goes the more you bent backwards. The deep saddles with pomels are very common to the Moors and they ride with short stirrups . Their steeds are ususaly galloping and rare ambling.Mongols , Ancient Greeks, Persians they all ride ambling- gaited horses with or without stirrups. I am not at all surprised that the great riders of renaisance do not mention ambling riding . Xenofon didnt also ! All the marble horses of Greek antiquity …amble!

allow me also a second comment. The ginetta bridle is a device where the curbed bit has no chain. There is a ring that works as a chain , and it is attached to the top of the curb. I recently found this bit in Greece , for riding ambling horses. They traditionaly used it to donkey stallions which they kept both as steeds on mountains and to breed mules from mares. The bit is very severe and pushes the upper jaw of the equine , also puts a lot of force on the lower jaw . The frightened and nervous look of many eastern horses ,in many old drawings ,is connected to this bit. It was in use in the eastern mediteranean for many centuries. Somewhere i read it is considered Byzantine invention. They had traditionaly many hot blood eastern horses to ride, the donkeys also!

Dear Nikolaos

first of all thanks for your appreciation. I find your comments very relevant. It is true that ambling was highly appreciated in the past, as it was considered more comfortable and suitable for long journeys on horseback. Amblers, which in Italian were called “chinee” (that is to say hackneys), were considered particularly valuable for this reason. So much so that, when Charles of Anjou conquered the Kingdom of Naples he reached an agreement (1265) with Pope Clement IV to offer him “unum palefridum album pulcrum et bonum” (a white palfrey, beautiful and good) every year, as a feudal homage (the gift was made even more pleasant by the addition of eight thousand ounces of gold per year…). This white palfrey was precisely a “chinea”, ie an ambler. This tribute was maintained until 1788!

I believe that the reason why the Renaissance treatises do not cite amblers is that those works were mainly devoted to the warhorse. Amblers were considered palfreys, namely horses suitable for public cavalcades and for traveling. The horses used in war were at the time different: destriers, who had an overwhelming force of impact, and coursiers who were actually faster and agile.

What do you say about the use of bits similar to the ginetta for mules in Greece it is particularly interesting and deserves definitely to be deepened. That kind of bit (which, as you rightly say, is particularly severe) is still in use in Africa (in the Maghreb, but also in several sub-Saharan countries). Bits similar to the ginetta were also used for mules in southern Italy. It would be worthwhile to compare them with the Greek type.

Thanks again for your interest in my work. I hope you will keep on following my blog and that we will keep in touch.

GB

thank you very much for your answer. Looking to the byzantine icons , [ the only remaining image of the eastern Roman empire] i see a lot of war horses , steeds of saints, that they are all of the light eastern type horse. Many of them amble. It is known that the heavy cavalry the ”clibanari ” used much heavier horses but generaly the horses of the eastern empire look like arabians , berbers, and high clas thoroughbreds. Ambling was as you said more important to daily use horses like palfreys, The famous statue Gatamelata, shows an excellent type of heavy ambling italian horse. I can send you two small foto of the gineta bit, from an old donkey stallion! [ send me a valid email please]. A similar one i have found selling, and i have seen in use, in the isle of Andros. The Isle has a rich medieval past, and a lot of naval families. I dont know if this was an imported bit or a remaining tradition of the past. The one that was in a shop was localy made .

What a lot of work went into this article! I’m impressed and enlightened in equal measure. Congratulations!

Thank you Joan. I’m very glad of your appreciation. I hope you will keep on following this blog.

[…] more on this, I recommend The Art of Riding on Every Saddle (a 15th century riding manual), and this article. So what were these horses? The mythos of the Spanish Jennet is not a modern invention. There are […]

Very interesting references and history. Being a Zenati, I know the history but really never knew how it was used and the time it was adopted. Thank you for the article. Best regards,

Thank you for this article and references. Interesting read indeed! As well as the comments

Thank you appreciation, Maria. I hope you will keep non following my blog.

I love the article… Love the picture of Stella!…. Compact & average hands..say 15 -151/2…. not like the way US always want to mess of every breed to be everything….horses were bred for their certain purposes…..in their region… Being Italian decent….Been with horses ,grandparent farm, riding, driving, etc….but never start serious compete until 65- my inner self chosed Andalusian…#1 my experience helping with a person who had a Stallion… but still inner…favor Spanish, I dance Flamenco, since I was 6yrs old:)..my gelding , Grey, 15 hds , no body wanted him..Being at clinics of trainers & riders….fits me…compact…temperment # 1 excellent…as trainer said….he doesnt forget… intelligence…being older competing…I call long leg riding my favorite…with harmony in all, me, horses gaits(judge to me once he looks like he is easy to ride:), western, Doma, Dressage, W. Dressage,love riding in Spanish saddle… fit right in:)…Trainer has done Jumping… now that we both are getting older, he 18 may…me turned 82…we kinda go on a slower pace…but still getting National, Reserve Points & Region 6 championships… mostly in West. Amat. ,new We. Dressage localy.. such a Passion for me. & love hearing from others in the same field.. Rosalie W.